By Emily Duggan

Granite State News Collaborative

When Elza Brechbuhl realized that The University of New Hampshire, where she is a junior and triple major in communications, women and documentary studies, wasn’t holding a peaceful protest for The Black Lives Matter movement, she decided to take action.

The yellow flyers are what Elza Brechbuhl passed out at the event.

She gathered friends together and made a Facebook page for the event that took place on June 7, and soon, around 800 UNH students and members of the Durham community came together on the Sunday afternoon.

The “Social Distancing Protest” was meant to serve as an educational event about the shootings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other victims of police brutality, according to Brechbuhl. She wanted the UNH community together in solidarity. As soon as UNH police found out about the event, they offered to donate bottled water and facial covering masks, she said.

Although the response to the event was mainly positive, some UNH students said that the university should have taken action sooner to provide a campus that is more welcoming to Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) students before the current social justice movements.

Conversations about race on campus became prevalent in spring of 2017, when UNH students partook in “Cinco de Mayo” celebrations around campus, wearing sombreros. A couple weeks after on May 13, a student drew Swastikas on a wall in one of the first-year dormitories.

“Administration should have started caring three years ago on May 5,” said Brittany Dunkle, a junior anthropology and justice studies major. “Racism erupted on our campus then, and I know that we still had Huddleston [former UNH President], but UNH has had plenty of time to begin fixing this problem and I’m sure they’ll shy away from it again.”

A Years-Long Call To Respond to Racism On Campus

The 2017 events launched “8 Percentspeaks,” an informal movement for BIPOC UNH students (who make up 8 percent of the UNH student body), to spread awareness about cultural appropriation. Members of 8 Percentspeaks made a list of 16 demands for the university to review, to ensure that the voices of BIPOC students at UNH were heard. The list was sent to former UNH President Mark Huddleston in spring of 2017 and was also made public on the group’s Facebook page. The demands included formally recognizing the Office of Multicultural Student Affairs (now The Beauregard Center) and requiring UNH police to undergo diversity training.

University of New Hampshire Police Chief Paul Dean ensured the student body in a June 3 statement that the UNH police underwent diversity and inclusion training in 2017 after 8 Percentspeaks made the request. The police force worked directly with BIPOC students, taking steps like requiring body cameras and increasing training, he said. However, Dean has still ordered a “complete review of our policies, training and tactics to ensure they align with evidence based best practices.”

At the protest, students listened to eight speakers, made up of students of color, athletes and members of the LGBTQ+ community. Students and community members walked to Wildcat Stadium. There, a video highlighted 1998 efforts of UNH minority students to bring “more attention to their reality” and broadcast quotes taken from the 2019 Campus Climate Survey, where students spoke directly about their experience as BIPOC on campus.

“UNH takes every opportunity to post pictures of the 1 percent to create this narrative of diversity that does not exist,” one student’s quote read, referring to the percentage of Black students on campus.

Allie Lester, a former UNH students and senior finance major who transfered to Southern New Hampshire University during the pandemic, shared that student’s concern.

“UNH used my photos for marketing purposes to show how ‘diverse’ our school is,” Lester said. “As a student of color, I just feel like it was an exploitation and misrepresentation of the school’s actual culture.”

Lester consented to the first round of photos as a first-year student before knowing where they would end up. When she became uncomfortable with it, she brought her concerns to a university counselor who told Lester, a New Hampshire native to “get used to it” as a person of color in New Hampshire.

“It had gotten to the point where if I am in a classroom, they will take pictures of me because I am the only African American in the class,” Lester said. UNH is fine “using her skin” to promote diversity, but “when it comes to offering assistance and safe places to people of color on campus, it is completely overlooked,” she said.

Addressing The Underrepresentation of BIPOC on Campus

According to UNH’s Institutional Research Assessment, as of fall 2019, the university only had 129 Black students, compared to 9,937 white students. Census data estimates that roughly 1.7% of New Hampshire’s population is Black.

From most recent data in 2018, Black students at UNH have a retention rate of 76.9% after their first year, compared to 86.1% of white students. Racial-ethnic minority and first-generation students feel a lower sense of “belonging” to the four-year institution that they belong to in comparison to their white peers, according to a Dec. 2019 study published in the journal Educational Researcher. Improving sense of belonging also improves student outcomes, study co-author Shannon T. Brady told Inside Higher Ed.

“We have found benefits on academic outcomes, benefits on health outcomes, benefits on engagement types of outcomes,” said Brady. “And what we know is that those are the kinds of outcomes that individuals care about, and also that colleges care about. We hope that this research really helps colleges think critically about how they’re going about their efforts to foster students’ sense of belonging on campus.”

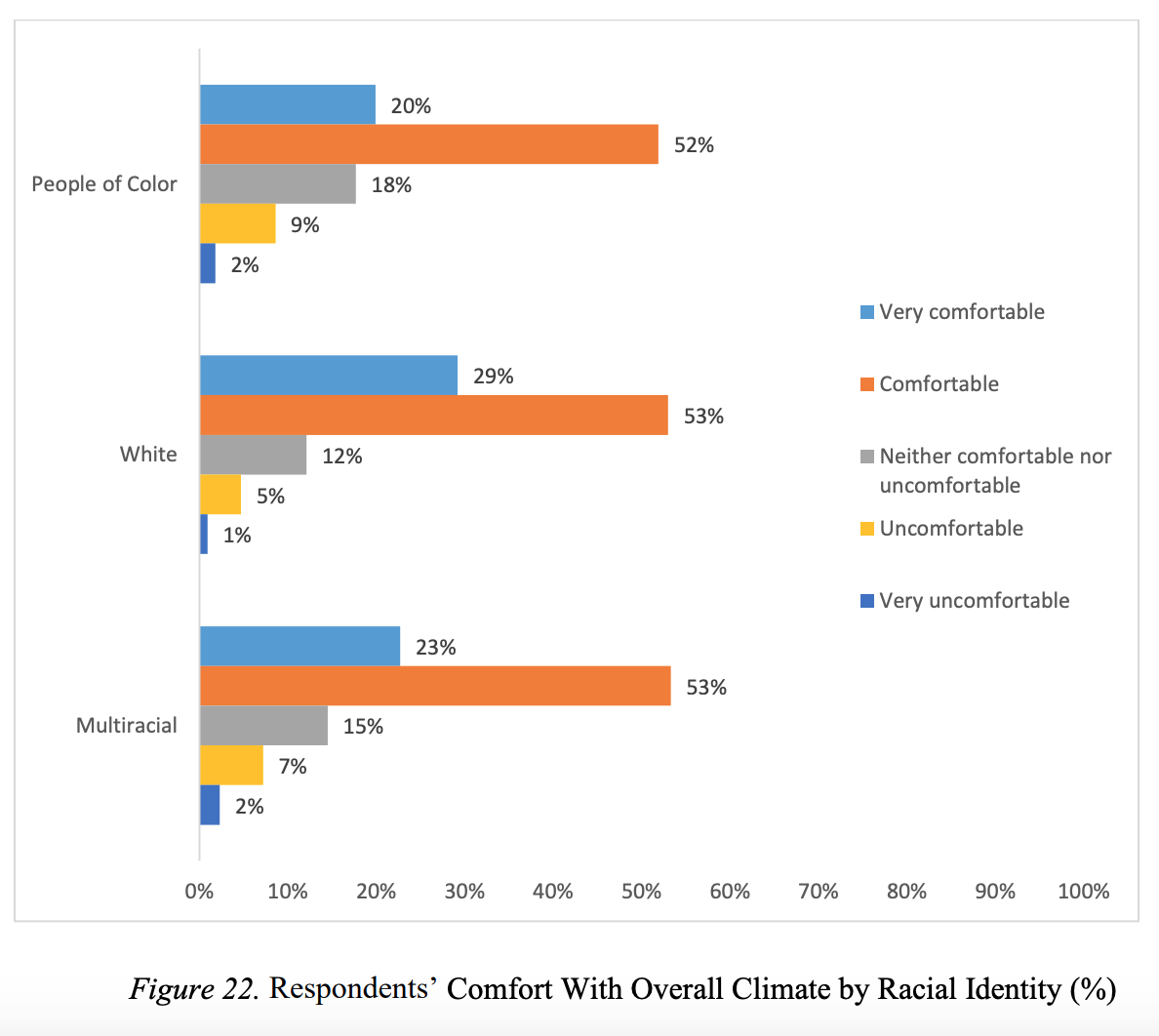

Only 20% of BIPOC students who participated in the Climate Survey felt “very comfortable” on campus, in comparison to 29% of white students. In addition, 9% felt “uncomfortable,” which just 5% of white students reported. The survey also had counts of bias-related incidents written into the report. It was designed to understand how a campus influences learning and development and whether or not there are discriminatory environments affecting students.

From UNH’s Climate Survey

“As a woman of color, I often feel that my opinions/comments are either overlooked or misappropriated,” one student’s response said.

Dr. Kabria Baumgartner, an English professor at UNH with a doctorate in African American studies, said that it “makes sense” that faculty, students and staff of color “may feel that the university has not done much at all to nurture a diverse and inclusive community.”

The pace of progress can be frustrating, she said.

“What I have seen, however, is that the university makes incremental progress, like a recent faculty cluster hire in women’s studies, but then it regresses, due to budget cuts or changes in administrative leadership,” Baumgartner said. “What is needed now, and what this moment calls for, is a clear plan followed by rapid implementation.”

She would like to see UNH hire more BIPOC faculty and staff, recruit students of color, and make programming and curricular enhancements. On her blog, Baumgartner highlighted ways that universities can recruit and retain faculty of color, including having anti-racism and anti-oppression training, rewarding departments with supportive environments for staff and faculty of color and having department chairs create “diversity initiatives” for the year.

UNH’s Response to Address Racism

In response to the peaceful protest that took place on June 7, University of New Hampshire President James Dean Jr., sent an email to the UNH student body that detailed a plan on how the university will address “systemic racism.”

The plan is two-fold, and will be carried out with assistance from the President’s Leadership Council (PLC). It starts with listening and learning through self-education by approaching relevant groups on campus and asking for input and feedback from students, faculty and staff.

The second part of Dean’s plan will take place in August after the PLC members educate themselves through the relevant resources. They will implement the lessons on campus and try to monitor the impacts of said learnings. Dean proposed an idea in his email on June 10 that would require students to take a required course on culture or anti-racism.

Dean was not the president of the university when 8 Percentspeaks made the list of demands for UNH. He did not become president until fall of 2018 and was formerly the vice chancellor and provost at The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

On June 17, Nadine Petty was named as the university’s chief diversity officer and associate vice president for community, equity and diversity. Petty’s experience will “play a critical role in helping us to identify the important steps we must take to create institutional change,” Dean said.

On June 7, UNH named Caché Owens-Vasquez the new director of The Beauregard Center (formally Office of Multicultural Affairs). Owens, originally from Green Bay Wisconsin, is a queer woman of color and a first-generation college student. She hopes that The Beauregard Center can become a “resource to people across the seacoast community,” she said, adding that research shows everyone learns more when they are surrounded by diversity.

“In New Hampshire, a predominantly white state, it takes intentional effort to create diverse spaces,” she said. “It is important to note that diversity alone is not enough, we need to create equitable spaces that are inclusive and safe for people of all backgrounds.”

She hopes to help create those spaces on and off campus.

“I want to support faculty in areas such as creating inclusive syllabi and facilitating difficult discussions in the classroom,” Owens-Vasquez said. “We are in an exciting time at UNH where we have an immense opportunity to be a national model for equity, inclusion and justice within other primarily white institutions (PWI).”

The Beauregard Center, located in the university Memorial Student Union, works closely with several student organizations and affinity based groups, according to Lu Ferrell, Owen’s colleague at the center. There are support groups specifically for students of color, and groups open to anyone, like the Native American Cultural Association and the Black Student Union.

“We also have three full time professional staff that work in the center that work to support students in any way that they may need,” Ferrell said. “That support may look like processing something that they are experiencing, or getting them connected to other campus resources that can also support them [BIPOC].”

From UNH’s Institutional Research Assessment

Students’ response

Colin Prato, a recent UNH theater graduate, has been vocal on social media about UNH’s response to educating its leaders on systemic racism. He believes that Dean’s plan is vague and thinks that the student body has yet to see an “outlined plan of legitimate action.”

“The way I see it, there are very clear common-sense prominent issues that require little to no ‘self-education’ to be able to reform,” Prato said. “There have been such vicious acts of racial hate and violence on this campus, and every time the university’s response is verbal without being practical. Every time we see a consistent lack of tangible support for our fellow Black and Brown students.”

Prato points out that UNH has two responding police forces -- their own and the town of Durham’s. He suggests that if UNH followed the trend across the country of “defunding police," the money that goes to the university police force could be redirected to improve UNH’s psychological and counseling services.

Allowing two months for Dean’s plan to move into fruition seems like a long time, Prato says. But Student Body President Nick Fitzgerald, promises that he will keep the racial equality in students mind’s as they return back to campus in the fall.

“Of course, this event did happen in the summer, but I have been in communication with The Student Collation and Black Student Union and have full intention on promoting change and making the conversation go into the fall,” Fitzgerald said. “I will work with them to make sure.”

Fitzgerald, a senior with dual majors in history and political science, said that he is going to set up a group of students focused on “anti-racism” with the goal of “eradicating racism” at the university.

“For decades now, the Student Senate has struggled to connect with students of color,” he said. “This focused group is for students of color in student leadership to come together to hear ideas and form policy.”

Brechbuhl, who organized the Social Distance Protest, would like to see UNH host a day dedicated to other cultures on campus, where BIPOC students can educate white students on their backgrounds through dance, music and food.

“They [many UNH students] grew up in small white towns, went to small white schools, and don’t put their head outside,” Brechbuhl, who is from Brazil, said. “They haven’t had that experience with culture.”

At the protest, Brechbuhl passed out fliers with information on how UNH students can educate themselves better on different cultures. That includes attending the frequent multicultural events at The Beauregard Center.

“UNH has to really work to bring different groups together,” she said. “Not, ‘let’s talk about race’ but ‘let’s get to know people in the community. A day for change, a day for people to come together and do stuff.”

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.