While complaints have been filed, the focus is on making affected businesses aware of the statute

By Daniel Sarch

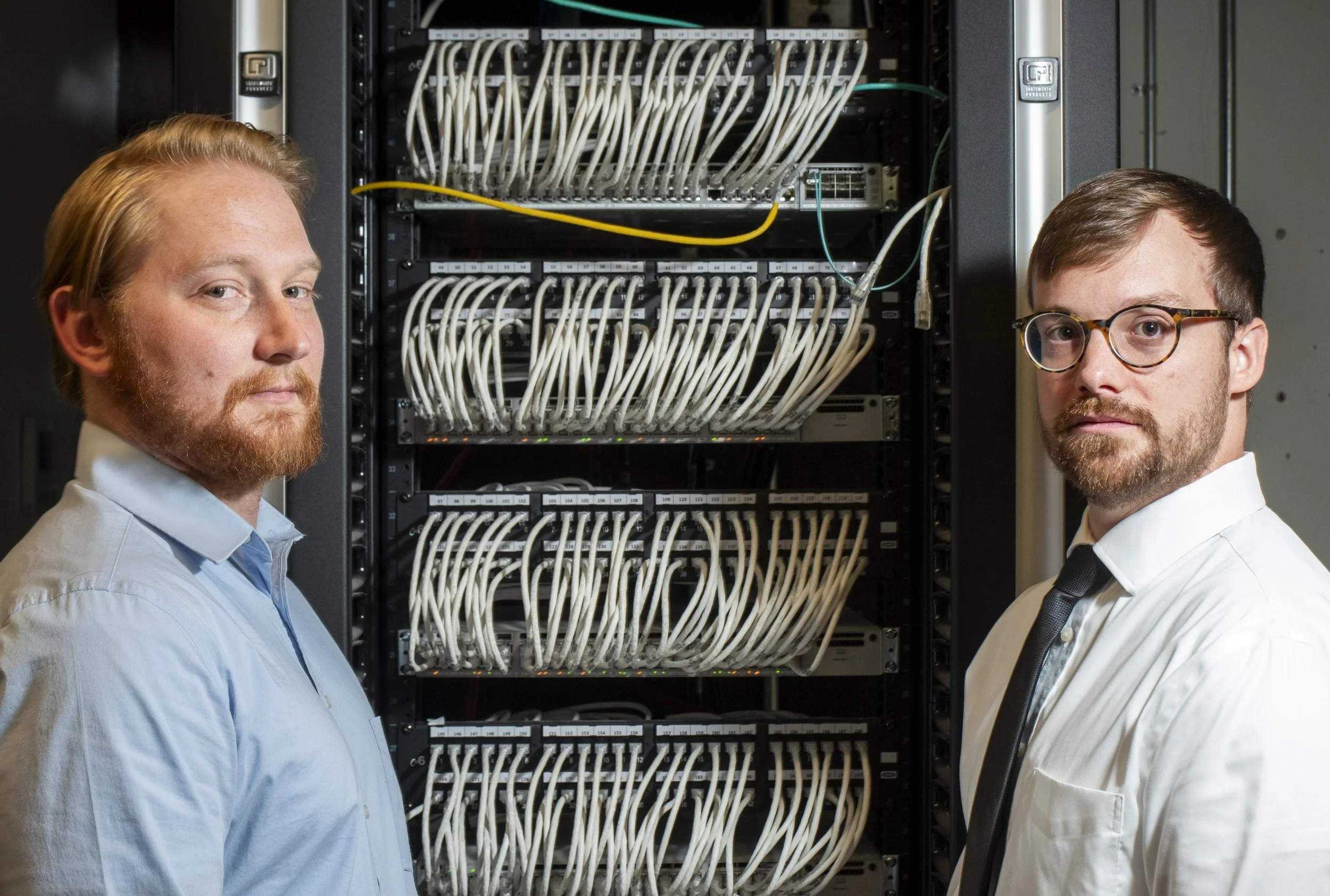

Investigative Paralegal Isaiah Hutchinson, left, and Assistant Attorney General Warren Cormack of the state’s new Data Privacy Unit stand in front of the data server in the Office of the Attorney General in Concord. The three- member unit is tasked with enforcing New Hampshire’s new comprehensive data privacy law. The third member of the unit, Investigator Frederick Lulka, was unavailable for a photo due to preparing and participating in several grand jury proceedings. (Photo by Daniel Sarch)

Nearly a year after New Hampshire’s comprehensive data privacy law took effect, the state’s new enforcement unit has received 27 consumer complaints — a sign of early awareness of the new law.

However, officials say much more work is needed to educate consumers and businesses about the new protections and obligations.

The law, which took effect on Jan. 1, gives consumers more control over how their personal data is used and puts certain responsibilities on businesses. For instance, consumers have the right to learn whether a business is storing their data, and if so, to request access to it, to obtain a copy of it, to correct inaccuracies, and to request that the data be deleted.

They can also opt out of targeted advertising, and the sale of their personal data or any profiling based on that data.

The law applies only to businesses that process the data of at least 35,000 consumers each year.

With the new law in effect, the Attorney General’s Office has formed a Data Privacy Unit that’s responsible for enforcing the law and responding to complaints.

Assistant Attorney General Warren Cormack, who heads the state’s new Data Privacy Unit. (Photo by Daniel Sarch)

“Not only are we receiving consumer complaints, but also as part of our work, we're going out and we're doing proactive data privacy enforcement by reviewing business policies and making sure that everything that they're publishing in terms of privacy notices and their business processes generally are operating properly,” said Assistant Attorney General Warren Cormack, who heads up the unit.

Other members of the three-person unit are investigative paralegal Isaiah Hutchinson and investigator Frederick Lulka. Cormack had previously worked in the AG’s Consumer Protection and Antitrust Bureau, focusing on general consumer protection matters. Hutchinson previously worked as a paralegal in the Medicaid Fraud Control Unit, and Lulka spent much of his career as a detective with the State Police major crime unit.

Investigative Paralegal Isaiah Hutchinson, left, and Assistant Attorney General Warren Cormack of the state’s new Data Privacy Unit shown in Office of the Attorney General in Concord, Sep. 23, 2025. Investigator Frederick Lulka was unavailable for a photo due to preparing and participating in several grand jury proceedings. (Photo by Daniel Sarch)

The trio are “sort of the tip of the spear” of the state’s data privacy enforcement efforts, said Michael Garrity, director of communications and external affairs at the N.H. Department of Justice. “If you have cases that need resources, you certainly would be able to pull other investigators in, or other agencies — partner agencies.” Those agencies include not just New Hampshire’s, but data privacy enforcement units in other states, too.

Working to ‘reach out’ to businesses

So far, Cormack said, the typical complaint involves concern that a business has a consumer’s information and is not deleting it as the new law requires, even after the consumer has filed a deletion request with that business.

For example, he pointed to a complaint involving a property management company. The consumer alleged the company was keeping their personal information beyond the date they left the apartment. The data privacy unit reached out to the business, which resulted in revisions in its privacy notice to include consumer rights, and the consumer’s data was deleted.

Investigative Paralegal Isaiah Hutchinson, left, and Assistant Attorney General Warren Cormack of the state’s new Data Privacy Unit stand in front of the data server in the Office of the Attorney General in Concord. The three-member unit is tasked with enforcing New Hampshire’s new comprehensive data privacy law. The third member of the unit, Investigator Frederick Lulka, was unavailable for a photo due to preparing and participating in several grand jury proceedings. (Photo by Daniel Sarch)

“When we reach out, it tends to be that they work with us really well,” Cormack said. “We're able to get a good result for the consumer and also put businesses in a better position to be able to honor those rights requests that are required under law now.”

So far, the Data Privacy Unit has not sued anyone as part of its enforcement efforts. During the unit’s first year, the law only requires the state to give notice of possible violation to any company and asks it to find a “cure” before bringing legal action. Companies are given 60 days to do so. But, starting in 2026, the state will not be required to allow companies that “cure” period.

Like any new law, there are growing pains. Since its formation, the Data Privacy Unit has been working to educate the public about the new law, including through Data Privacy FAQs for consumers and businesses.

But the main problem with the law’s rollout is that it remains relatively unknown, said attorney Cameron Shilling, director of the litigation department and chair of the cybersecurity and privacy group at the Manchester-based law firm of McLane Middleton.

“The majority of businesses are unaware of this law, and an even greater majority are unaware of what this law does, or how to comply with it,” Shilling said.

Investigative Paralegal Isaiah Hutchinson, left, and Assistant Attorney General Warren Cormack of the state’s new Data Privacy Unit shown in the Office of the Attorney General in Concord on Sept. 23, 2025. A third member of the unit, investigator Frederick Lulka was unavailable for a photo due to preparing and participating in several grand jury proceedings. (Photo by Daniel Sarch)

With something as abstract as data privacy, Shilling said, some businesses are slow to realize that they must comply with the law. Some businesses have budgetary concerns, he said, and while they allocate money for marketing, client outreach, sales and capital expenditures such as new computers and servers, the benefit of investing in data privacy compliance is not always so clear.

“Businesses prefer to buy things that are tangible,” Shilling said. “Businesses believe that cybersecurity and privacy, at least superficially, is not making them any money. That's just going to cost them money.”

Some businesses have not built data privacy into their management structure. It doesn’t belong in the job description of a chief executive or chief financial officer or a vice president of sales or operations or quality control. Nor does it fall neatly within the IT department.

But Cormack said the law need not require most businesses to go through a major restructuring. Sometimes t’s as simple as handling rights requests through email.

“As long as you're doing it within the statutory timeframe, and you're doing it in response to consumer concerns, and you're doing it in compliance with the statute … that's a totally reasonable way of operating,” he said.

Easier to comply

Investigative paralegal Isaiah Hutchinson, a member of New Hampshire’s new Data Privacy Unit staff. (Photo by Daniel Sarch)

Shilling compared what is happening with data privacy with the dawn of cybersecurity awareness in the early 2000s, when businesses began switching from paper to digital records. It didn’t become a serious consideration until the 2005 data breach of ChoicePoint, one of the nation’s largest data brokers, that compromised the personal information of more than 163,000 consumers, and resulted in 800 cases of identity theft.

A settlement in 2006 required the company to pay $10 million in civil penalties and $5 million in consumer redress. That incident also led the nonprofit Privacy Rights Clearinghouse to begin tracking data breaches in 2005. It has since documented over 75,000 data breaches.

Data privacy awareness has been on a similarly slow track. The first widespread data privacy law was enacted by the European Union in May 2015, but didn’t become effective until three years later. The United States had few regulations on data privacy until California passed the California Consumer Privacy Act in June 2018, which took effect in 2020. Since then, 20 states have now enacted their own data privacy laws.

Shilling believes it was the data breaches that led businesses to pursue proper cybersecurity measures, and worries that it might take a similar crisis to bring about adequate data privacy responsibilities.

“At some point in time, we might see plaintiffs, lawyers and class action lawsuits enforcing privacy laws,” he said. “But we're not there yet, and I'm not sure whether or not we're going to be there anytime soon.”

But with more and more states passing these acts, businesses will become more aware, Shilling said, and because New Hampshire’s law is like many other states’ laws, it will be easier for businesses to comply.

“New Hampshire did a good thing by choosing to adopt a law that comes from other states,” he said. “Instead of having a patchwork of state laws, you have a synergy of state laws. It also is good in that it's fairly detailed.”

These articles are being shared by partners in the Granite State News Collaborative.Don’t just read this. Share it with one person who doesn’t usually follow local news — that’s how we make an impact. For more information, visitcollaborativenh.org.